Another study which explored and expanded on the ‘seductive allure of neuroscience explanations’ (SANE) phenomenon. SANE “is the finding that people overweight psychological arguments when framed in terms of neuroscience findings” (p1). That is, inclusion of irrelevant or flawed arguments using visual or verbal descriptions of neuroscience findings and brain images etc. lead to people rating the quality of the arguments higher.

The authors nicely cover some of the background on the SANE effect and potential reasons why it may have this effect.

- One explanation is that “neuroscience offers seemingly simple explanations of frustratingly complex cognitive and emotional phenomena … [where the finding] that ‘behaviour or thought X “lights up” area Y’ is a deceptively simple ‘explanation’ of what can be a complex psychological process” (p3).

- The fascination that people have with brain images, which are more likely capture attention than other sources of info. Two studies found that participants rated the scientific articles to be of higher quality or higher credibility when the articles included detailed depictions of the brain structure or more realistic 3D brain images versus schematics or 2D images.

This study focused on educational neuroscience, which is aimed at applying neuroscience to improving student learning. It’s noted that some popular media articles “are sometimes incorrectly linked to educational recommendations of dubious value and accompanied by colourful brain images” (p3).

This study answered the following three questions:

- Is there a SANE effect among the general public when popular articles about psychological findings cite extraneous neuroscience findings to justify their arguments

- Whether SANE varies as a function of the findings and topics themselves

- Individual differences in the SANE effect

245 participants were engaged in the survey. Several research conditions were employed, but in short the authors had educational articles that spoke about psychology principles, and then added irrelevant/extraneous neuroscience findings to some of the articles and then asked participants to rate the credibility. Then they compared how the irrelevant neuroscience info altered the perceived credibility.

Results:

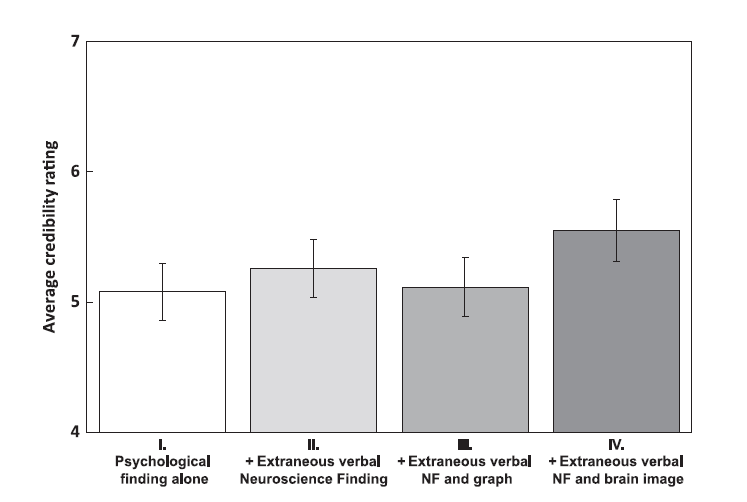

SANE effects weren’t consistent across the study conditions. For instance, there was no credibility effect when either verbal neuroscience descriptions or brain images alone were added to the educational topics. However, there was a SANE effect when educational topics were combined with extraneous neuroscience verbal descriptions and images together. The image below nicely shows the findings.

The authors note that this finding “is consistent with prior studies showing that the SANE effect is driven by the presence of rich depictions of brain structure and function as produced by MRI and fMRI, respectively” (p10-11).

Said differently, irrelevant or incorrect neuroscience framing (as verbal or written descriptions and of brain images etc) seem to only affect perceived credibility in the richest of conditions where these methods are combined.

For individual differences in the SANE effect, a positive correlation was found between the familiarity of the education topic, attitude towards psychology and knowledge of neuroscience on the credibility ratings of articles. This was said to be expected, where:

“people evaluate scientific arguments more positively when the conclusions are consistent with their prior beliefs. It is also consistent with two findings in the judgement and decision-making literature: confirmation bias, or the tendency to positively orient towards information that aligns with prior beliefs (Nickerson, 1998); and the availability heuristic, or the tendency to make judgements based on the information most readily accessible in memory (Tversky & Kahneman, 1973)” (p12).

One inconsistency with this study compared to a previous study is the effect among neuroscience experts. A previous study found that neuroscience experts were less susceptible compared to novices to the SANE effect. It’s speculated that the previous study had experts with a deeper knowledge, and thus less susceptible.

The current study relied on a sample from the general public. Here, the SANE effect persisted even when controlling for individual differences (familiarity, attitude & knowledge). It’s said that there’s a unique role in neuroscience framing when the general public evaluate the credibility of psychological findings to educational topics. This “apparent authority of neuroscience framing is consistent with the finding that among undergraduates, neuroscience is more admired than natural science, psychological science, and social science disciplines (Fernandez-Duque et al., 2015)” (p13).

I think this series of studies are really interesting on SANE. It seems to have some positive benefits in learning and combatting mis/disinformation (e.g. vaccinations, anti-science conspiracies) – where embedding a rich set of neuroscience images and descriptions may help convince people of credibility.

It may also have negative effects, as these studies have demonstrated, where mis/disinformation also increases credibility of arguments.

Authors: Soo-hyun Im, Keisha Varma, Sashank Varma, 2017, British Journal of Educational Psychology

Study link: https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12162